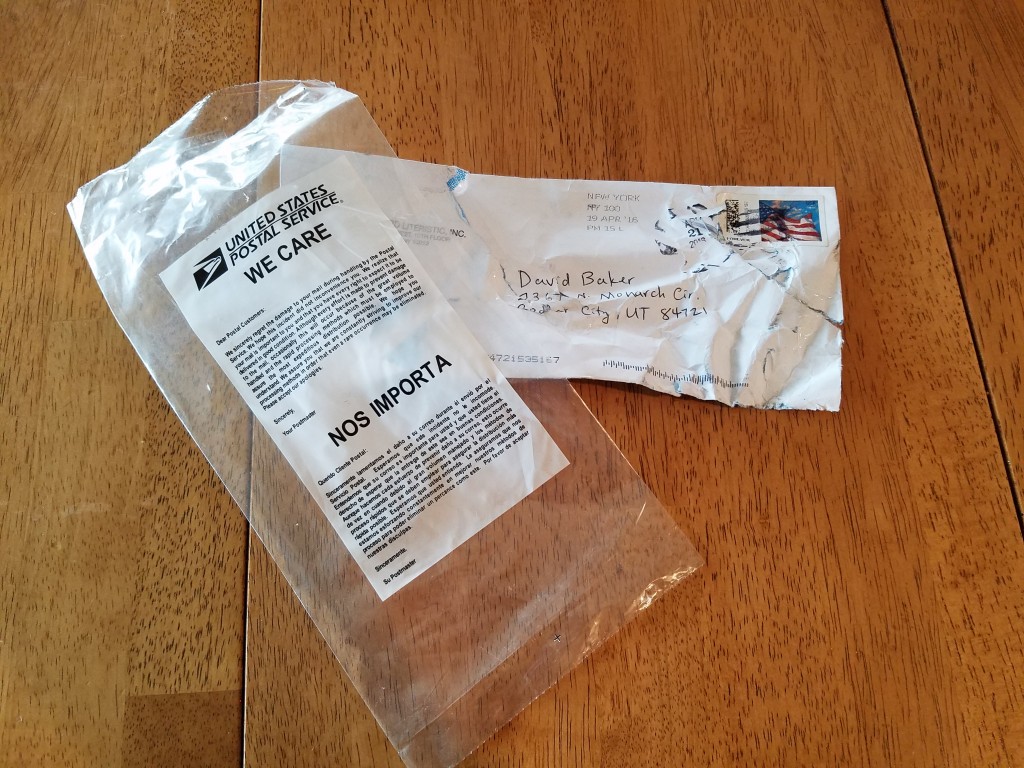

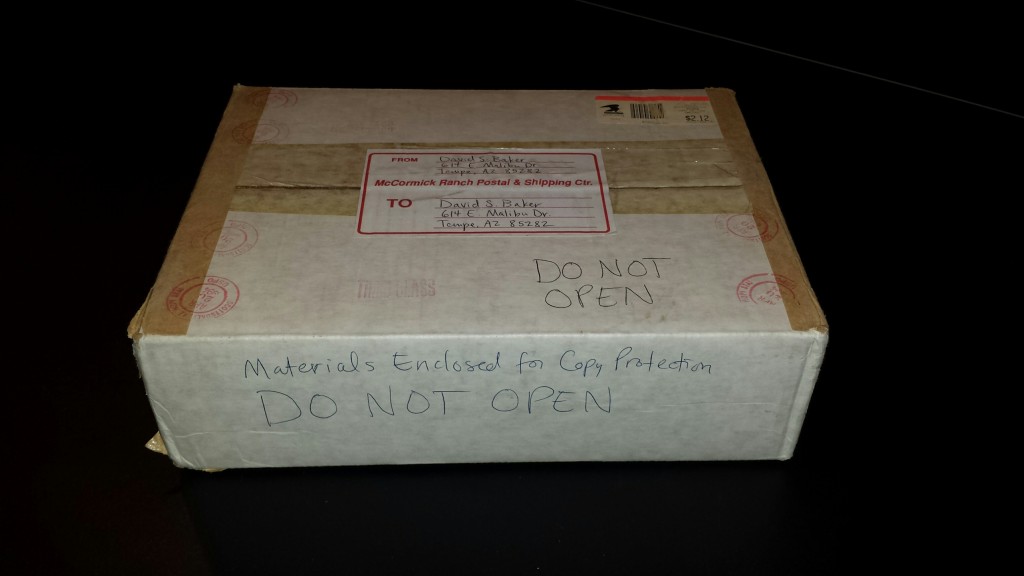

There’s this box sitting in my basement. I’ve been carrying it around for 22 years.

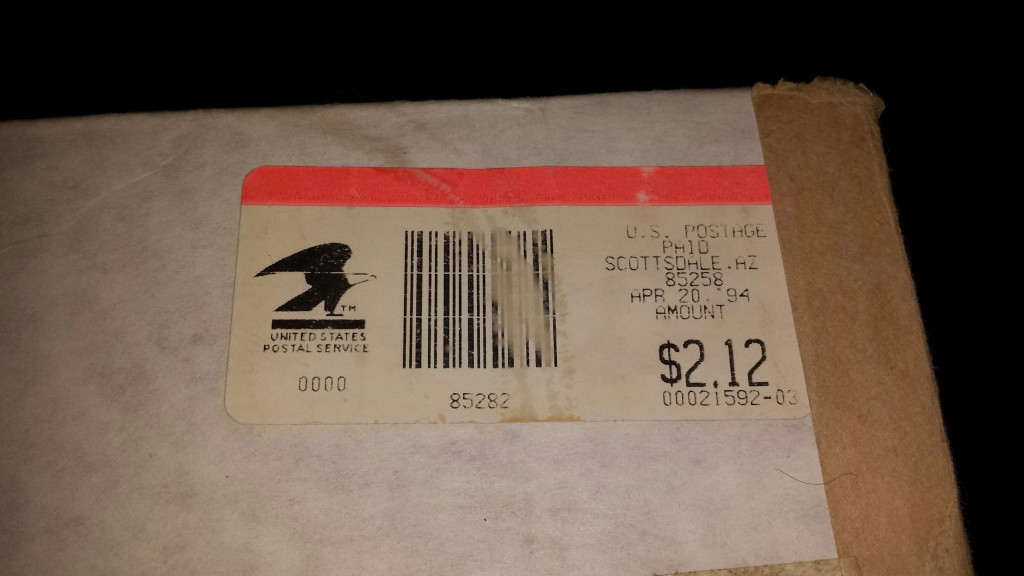

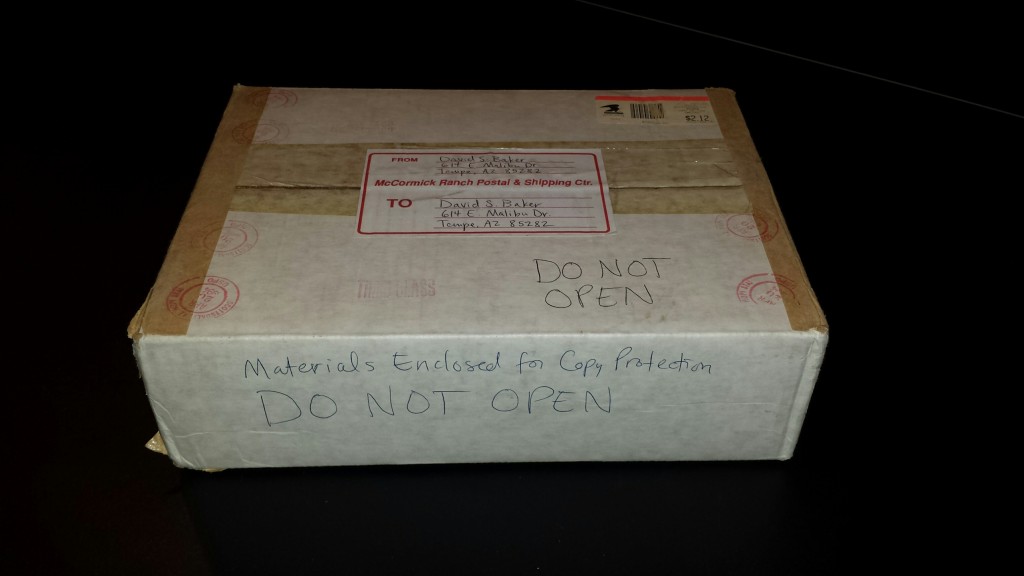

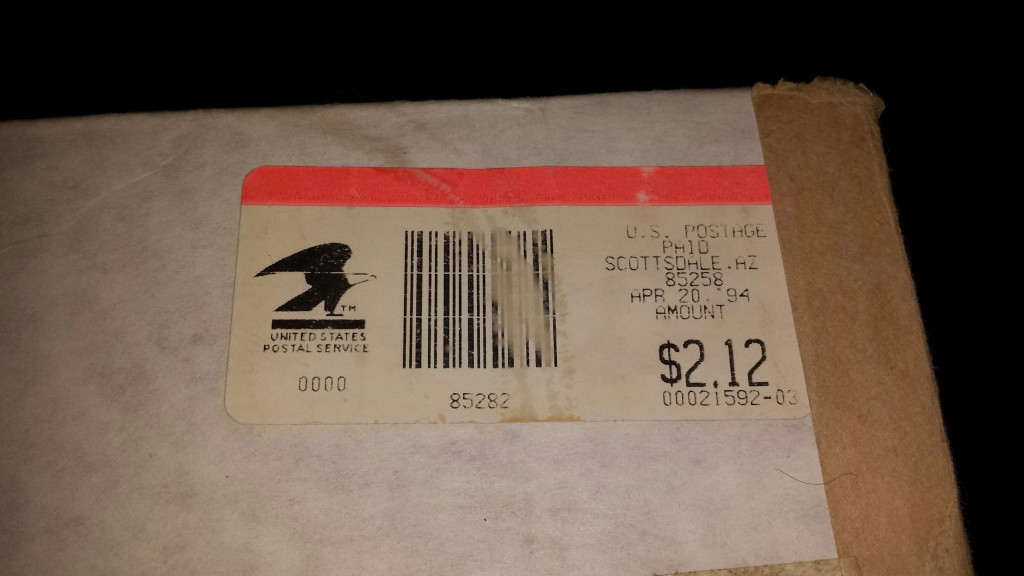

It’s a white media box, sealed with paper tape which some helpful post office worker stamped like crazy with his date seal. I was living with my aunt and uncle when I originally sent it, and both the TO and FROM addresses point to the same address in Tempe, Arizona. The meter is postmarked April 20, 1994—just when Ace of Base’s “The Sign” was getting a lot of initial airplay and The Hudsucker Proxy was still in theaters:

Every once in a while, I look at the box and think, “Why haven’t I opened this thing after all these years?”

Good question.

Poor Man’s Copyright

Someone told me once, a long time ago, that the best way to protect creative materials is to seal them up and send them to yourself, then keep them unopened.

The idea, I guess, is that if Sneaky McStealer happened to find one of my masterpieces, ripped them off and turned them into a major motion picture blockbuster or a New York Times bestseller, I could take McStealer to court for infringement of intellectual property.

How It’s Supposed to Work

I can just see it now. My lawyer gets McStealer on the stand and asks him where he came up with the idea for “his” movie. He lies through is teeth and says it was his original idea. Then plaintiff’s attorney brings in this battered box and sets it on the railing in front of the defendant. I can see it now…

Attorney: Mr. McStealer, what is the postmark on the box in front of you?

McStealer: Looks like April 20, 1994. It was a Wednesday, I recall…

Attorney: Please, just answer the questions, sir. And does this box show any evidence of having been opened?

McStealer: (glaring suspiciously across the courtroom) Uh, no, I guess it doesn’t.

Attorney: (producing an X-acto knife.) Would you please open that box, Mr. McStealer?

Sneaky McStealer slits open the paper tape and opens the box. With his back to the defendent, plaintiff’s counsel asks the next question.

Attorney: And can you tell the court, Mr. McStealer, what’s inside that box?

McStealer: It’s a copy of that screenplay I st— I mean, I wrote.

Attorney: Can you please tell us, sir, how it is that the screenplay you supposedly wrote in 2016 happens to be inside a box sent to David S. Baker in 1994?

Music hit: Dum dum DUUUUMMMM!

The slimy rip-off artist opens the box and—voila!—sitting inside is the novel that made him millions. Sneaky swallows. He looks at the judge. He looks at me, then slowly raises his hands.

McStealer: Okay, okay! I admit it! I snuck into his house and stole that old novel and claimed the story as my own. I’m sorry, Mr. Baker, I really am. I’ll dedicate my life to making sure you get the credit for your brilliance!

It Doesn’t Really Work

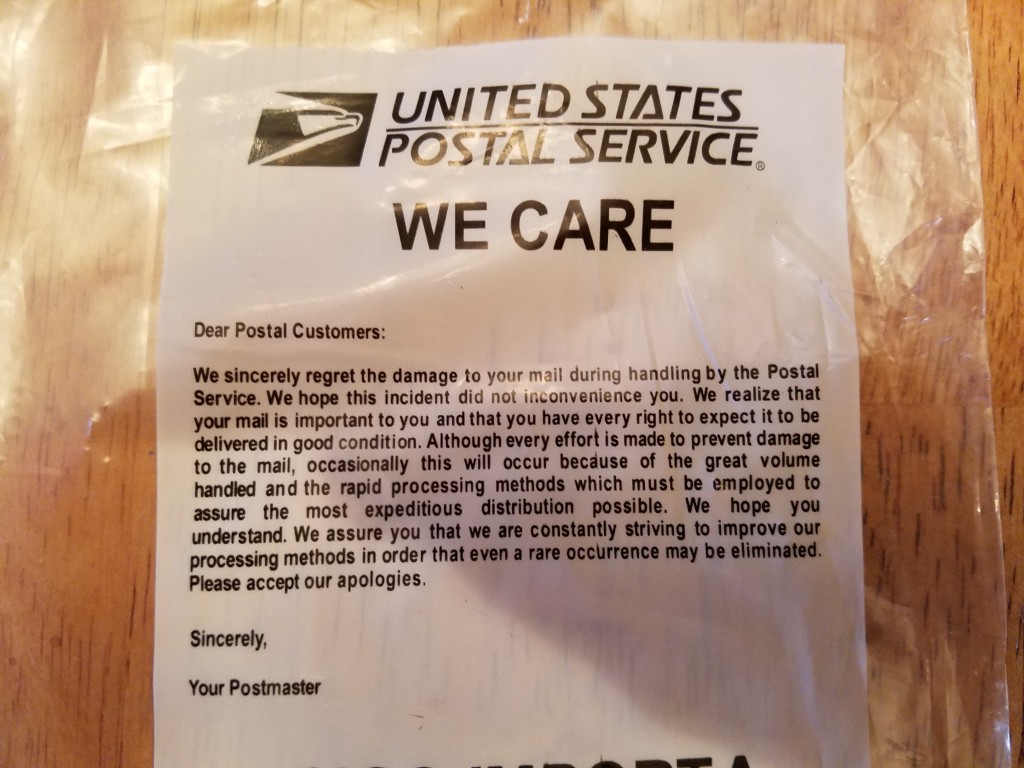

I guess that’s what I was thinking, anyway. The problem is, it doesn’t really work. According to copyright.gov:

I’ve heard about a “poor man’s copyright.” What is it?

The practice of sending a copy of your own work to yourself is sometimes called a “poor man’s copyright.” There is no provision in the copyright law regarding any such type of protection, and it is not a substitute for registration.

Of course, that’s from the government. What the heck do they know? But even Snopes.com, Internet debunkers extraordinaire, have weighed in on the topic:

Mailing one’s works to oneself and keeping the unopened, postmarked envelope as proof of right of ownership to them (a practice known as the “poor man’s copyright”) has no substantive legal effect in the U.S. We’ve yet to locate a case of its use where an author’s copyright was established and successfully defended in a court of law by this method. At best, such mailings might serve to establish how long the author has been asserting ownership of the work, but since the postmarked-and-sealed envelope “proof” could be so easily circumvented, it is doubtful courts of law would regard such evidence as reliable.

Oh.

Rats.

Copyright Basics

The thing is, anything you or I write today is automatically copyright. It might not be registered, but it’s automatically protected from the moment of its creation until 70 years after you or I die.

We don’t even have to write “Copyright 2016” and try to remember the weird Windows Alt-code for the copyright symbol (or the HTML character entity, if we’re working on the web). But for the record, in Windows you hold down the Alt key and type “0169.” If you have a Mac, it’s Alt-G. In HTML, it’s “©” or “©.”

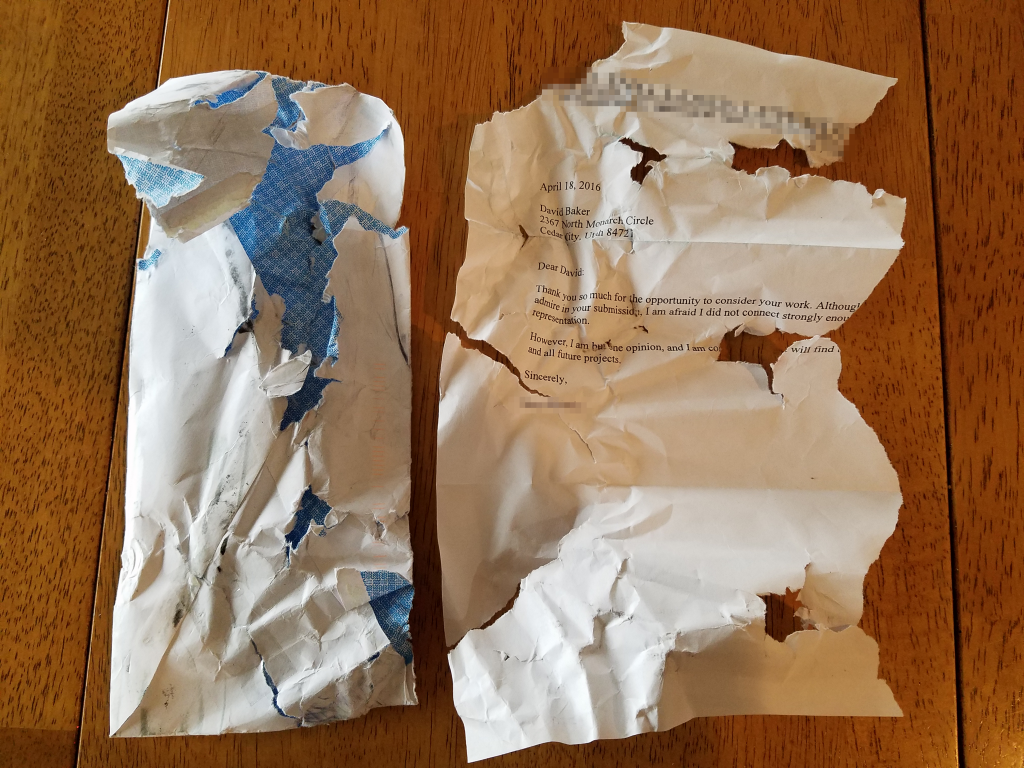

What’s in the Box?

Here’s the funny part. I have no idea what’s actually in that box. I honestly can’t remember. I have to guess it contains the screenplay I wrote that year (the one that’s already been made into a movie). My one-act play Inside Al might be in there even though it’s already registered with the copyright office, plus several other plays I wrote as a high schooler and colleger. The two novels I wrote in my teens, one of which won an honorable mention for the Avon Flare Young Novelist contest, may be in the box as well.

What else? Essays from my early years? Poetry, heaven forbid? What else is in that darned box?

Still Unopened

I don’t have any idea … and I won’t likely know for a long time, because I can’t bring myself to open it. Don’t ask me why.

So here’s my commitment. I’ll open the box on the day I get my first novel published—the day I go into a bookstore and find a book I’ve written sitting on the shelf. When that finally happens (and I think I’m getting closer) I’ll get a camera rolling and do an “open box video” of my little time capsule of sad literary output.

Stay tuned…