Our family recently had a chance to contribute to a production of Aladdin Jr. put on by Cedar City Children’s Musical Theater. My wife was the musical director and all three of my teenagers were in lead roles. After I kinda sorta designed the set, made some props and agreed to lay out the program, the director asked me to take care of a special project: the Cave of Wonders.

The project was affectionately dubbed the COW.

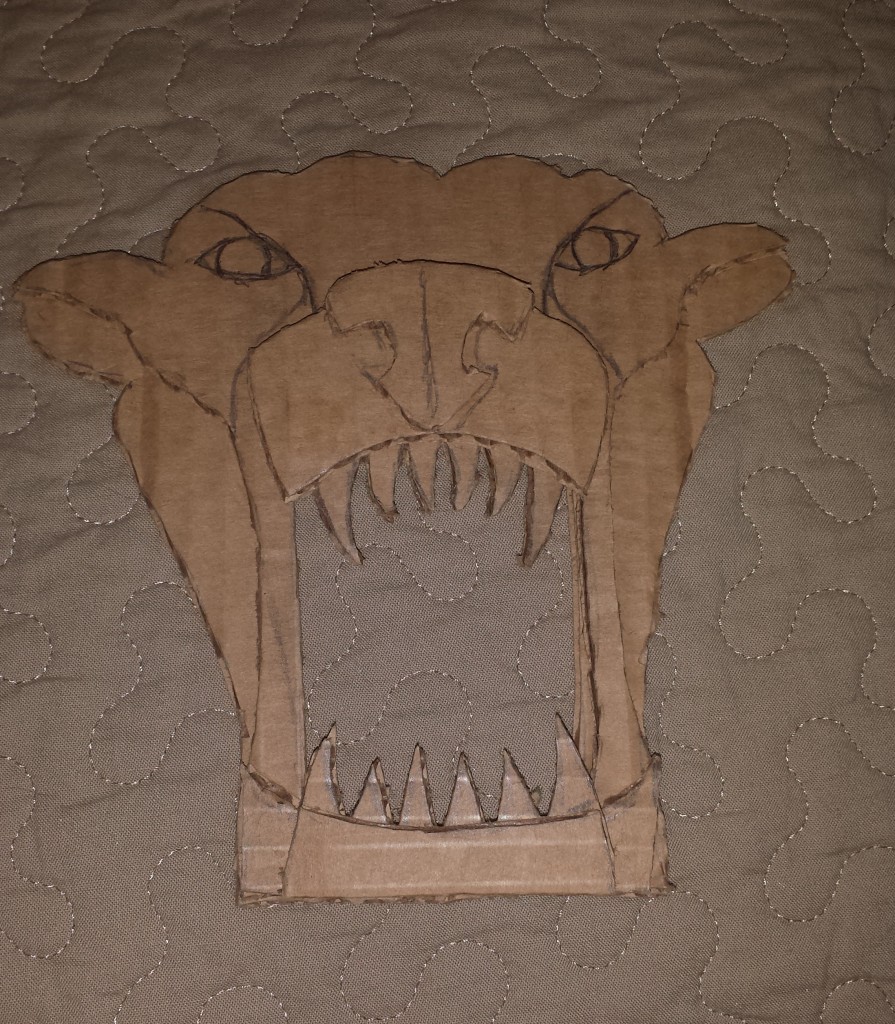

The picture above was the vision the director gave me to realize on stage. We knew we couldn’t make it 30 feet tall, but we wanted as big as possible. There were basically three requirements:

- We wanted it to be as large as possible so it came off as impressive rather than pathetic.

- We wanted the mouth to open and close.

- We wanted the eyes to light up on demand.

- The opening needed to be large enough for the actors playing Aladdin and Abu to fall through, in order to enter the cave where they find the Genie’s lamp.

- We knew the piece would have to fly in and out on wires, so we knew it had to have a fairly narrow profile (about 18 inches total). That limited the number of foam layers we could use in building up the piece.

I documented the construction process, taking pictures at various steps along the way. I thought this might be helpful to someone else doing the show.

Before beginning the actual construction, I did a cardboard mockup to figure out how the height of the snout impacted the height of the opening.

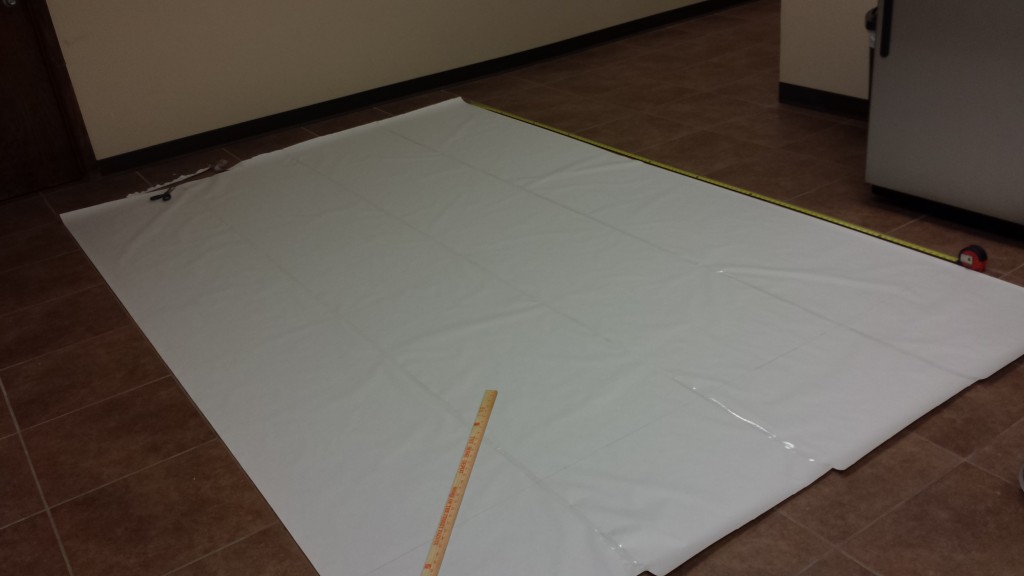

Sadly, I didn’t have access to butcher paper, which would have made the templating process much easier. Instead, I visited the local newspaper office and bought a 22-inch-wide roll of paper for all of two bucks. Taping four strips together got me a manufactured sheet almost eight feet wide and about 12 feet tall.

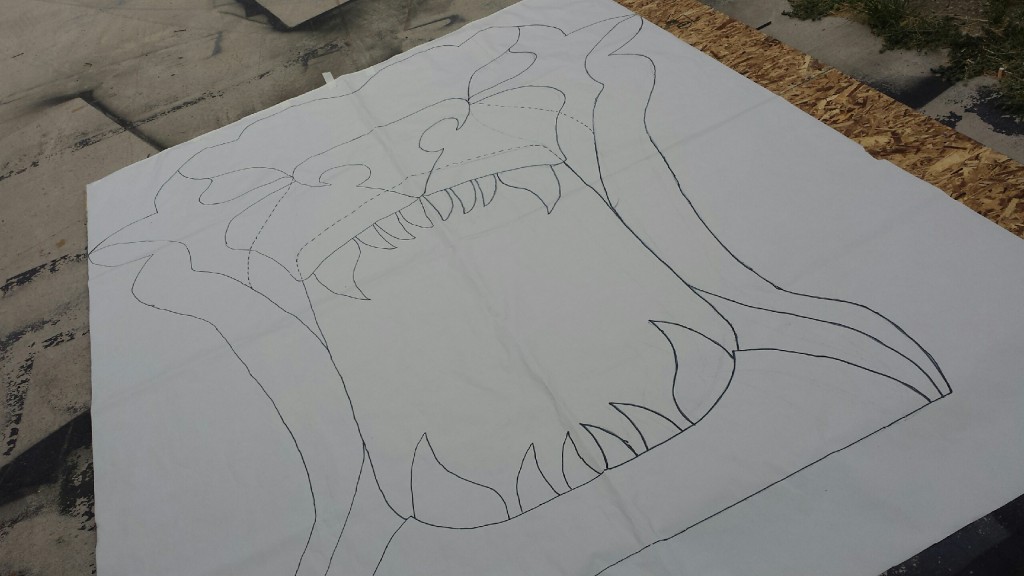

I taped the sheet to the wall and used my laptop and a projector to throw the image up onto the paper like a screen. Then I used a trick I learned a long time ago. I traced just half of the image onto the paper. Bear with me on this.

After tracing just one side of the image in pencil, I took it down and went over the lines with a Sharpie. Then I flipped it over and traced the same image on the reverse of the paper, also in Sharpie. Then I folded the paper in half with the right side out and traced the other side using the reverse-side transfer. Unfolded the paper and voila! … a perfectly symmetrical design. Here’s what it looked like before I made my sub-templates:

Before cutting it apart, I made a few smaller cutting templates using the same paper roll. (That two bucks was a good investment). I made a template for the snout, one for the noise, plus templates for the lower jaw, upper and lower teeth, brow and ear-eye overlay, and the lower jaw extensions. Then I cut out the outline and transferred it onto two and a half sheets of OSB (oriented strand board).

After that it was time to give the COW some structure. I gave it a frame made of 2x4s. The photo below shows the frame as we originally built it. I actually tilted the framing members to avoid the mouth opening and light reflectors. We eventually changed this, redesigning the frame so that we could mount the drawer tracks on the 2x4s themselves. They had to be parallel for that to happen. I’ll have to see if I can get an updated photo showing this.

You’ll notice that the back of the eyes are made from the reflectors of a couple of aluminum clamp lights. I removed the clamps and attached the reflectors to the back of the COW with cable staples. We left off the actual light sockets until the piece was finished. I put an electrical receptacle on the back so the two lamps could be plugged in. These were connected inside the box to an extension cord, which was later plugged into another extension cord hanging down from the flies.

Before I could do the foam, I needed to do the teeth. I decided to make the teeth out of foam rubber instead of construction foam. My reasoning: when actors fall through the mouth, it was super likely that at one point they would hit a tooth or two. Since construction foam is notoriously fragile (prone to dents and chips and breaks) I wanted something that would “bounce back” if Aladdin or Abu clipped it on the way through. Foam rubber was the obvious choice.

I had on hand a sheet of foam rubber that was twice as thick as I needed. So I first sliced it down the middle with my main tool (a steak knife I stole from our camping utensils). Then I cut out the teeth by sawing them with the knife, and shaped them with snips from a pair of scissors. These photos show the upper and lower teeth taking shape.

With the COW’s dental work taken care of, I could begin cutting construction foam. For this project I used five or six sheets of two-inch white construction foam board, which I sourced from Home Depot at about $22 per 4×8 sheet.

The foam comes with a white plastic coating on one side and a plastic/foil coating on the other. Before working with the foam, we had to remove the coatings from both sides. Basically, you peel up a corner and work from the outsides in, heating the plastic slightly with a heat gun as you go. It took some time, but it was worth it to be able to use the cheaper material.

Once the foam had been denuded, I traced the shapes from the paper templates. I then cut out the pieces with my handy-dandy steak knife. For two layer pieces like the nose (pictured below) I cemented the pieces together with wood glue. To make the foam layers adhere to the OSB I used Liquid Nails construction adhesive.

Here’s the snout piece taking shape:

Here’s the COW with almost all layers in place:

Here’s another view. The only pieces left to put on are the ear-eye overlay and the brow. Sadly, I forgot to take a photo of the full piece before sculpting.

I used just a few simple tools to sculpt the contours into the foam. Rough rounding was all done using my handy-dandy steak knife. For a rounded corner I would hack off the 45-degree angle, then shave off the hard corners. At that point it was easiest to hit the cuts with my heat gun. This firmed up the cuts (actually making the foam harder where the heat was applied) and softened them at the same time.

Once the basic shape had been achieved, I would soften and refine the shape using a simple shoe rasp. My rasp has both flat and rounded profiles, medium and fine teeth. I used the fine and flat for most of the sculpting. Here’s the mostly final shape:

The eyes involved high-powered exterior floodlamps, which we wrapped with red lighting gels. I cut apart an old clear plastic bin and made “lenses” by cutting them out with my Dremel tool. I painted the COW with a tan-colored paint and added some shadowing and contour lines to give it a little more depth. We hung it from a boom with heavy-duty wire. The theater electricians ran power to the

This was the first test we did. I still hadn’t finished painting the teeth, but we needed to get the sucker hung so the kids could begin practicing with it.

Below is a video of the Cave of Wonders in action. It wasn’t onstage for very long, but I think overall it was worth the effort.

Update on Mechanics

A reader (Mary McKenney) asked for details on how the mouth opens and closes. Here’s how it works:

The snout and upper jaw piece is screwed to 2×4 pieces that attach to some 1/2″ plywood cutouts that mount onto standard drawer tracks. Look closely and you’ll see that the plywood is notched and so is the upper opening (top of the picture). This gives the mouth an extra three to four inches of travel, allowing the mouth to open wider.

The drawer tracks are mounted on the 2×4 framing. (Note that I repositioned the 2x4s from the photo above so they would be perfectly parallel. Otherwise the slides wouldn’t work.) A pulley mounted on the top framing member allows a rope to be pulled to raise the upper jaw. Also, if you look at where the rope kind of rubs against the upper opening I cut out a notch in the wood to give it easier up and down play.

The rope attaches to a screweye that’s stood off from the snout backing with a scrap of 2×4. Luckily, I thought to attach this with screws from the other side before I applied the foam. Much sturdier that way.

With the help of my trusty assistant, I made a very professional-grade video to show how it all works.

Another Great Example

Reader Mary McKenney provided some pictures of her own Cave of Wonders project, inspired by this blog post. Great work, Mary!