I have been involved in theater for much of my life. I have directed shows, served as assistant and musical directors as well as stage managers. I’m actually a published, award-winning playwright (though that happened long ago). I actually have a degree in theater (A.A.). Offstage, I’ve built sets and props, painted backdrops, sewn costumes, played in pit orchestras, and designed programs and publicity. It’s safe to say there’s not a job in theater that I haven’t done.

I wanted to say something about probably the most baffling aspect of theater: casting. Let me state right up front that this is my opinion. Others may have different perspectives, and that’s okay.

Primary Casting Considerations

Straight plays: When it comes to non-musical theater, a role should always go to the person who can most convincingly portray the character as envisioned by the director. Physical characteristics (whether the actor is male or female, tall or short, thin or fat, attractive or not) are often a consideration, but they usually shouldn’t be primary. The play’s the thing, as the Bard says, and casting should involve putting the best available actor to play the part.

Musicals: For musical theater, priority should be given to the person with the most appropriate singing voice for the role. Especially for lead parts with a lot of solo singing, it’s critical that the actor’s vocal range, quality, and singing ability be matched to the part he or she will be playing. For certain roles, dancing could possibly edge out singing as the most important quality. Apart from that, though, everything else—including looks and body type and so on—is secondary to the voice. Audiences attend musicals to hear the music, and nothing does more to spoil a musical than a substandard voice in a leading part.

(And yes, Russell Crowe, we’re all looking at you.)

School Productions

For school-sponsored shows, the people doing the casting have a few other things to think about. Is the student struggling academically? Is the student in sports or other activities that could conflict with rehearsals? How is the student’s attitude and work ethic? Has the student been flaky in the past, dropping out of or under-performing in other roles?

While these considerations can impact a director’s casting decisions, the primary ones—acting ability for straight plays and singing ability for musicals—should still receive the heaviest considerations.

Not everybody agrees with this. A while ago, a friend of mine co-directed a school musical. Her co-director insisted on giving the lead role to a kid who was (and I’m allowed to say this because I’m not an educator) a complete and utter douchebag. “Giving so-and-so the lead would be good for him,” her co-director whined. “I just know he will rise to the occasion!” Other things being equal, the co-director believed in giving choice roles to students who earned them through hard work and positive behavior. The co-director overruled her, and the entire production (and the entire cast) suffered.

More recently, one of my teenagers was cast in a role that was very much against type. At the same time, a major lead role was given to a kid who was basically a non-singer. He had no ear, and an incredibly limited vocal range. During each performance, we sat and cringed as this actor tried (and failed) to hit the notes required by the part. When we asked the director about the decision to match that actor to that role, the answer was, “He just really needed it.”

I’m sorry, but no. Theater is (or can be) about personal growth. But casting an inadequate singer in a lead role (whether the actor needs it or not) is simply audience abuse.

Community Theater Productions

Another special case is community theater. This usually involves small, under-funded, under-staffed groups who do theater as a labor of love. The better groups often attract top talent, while other groups actually have to beg people to audition. (The Facebook post here is a sad example.) Casting decisions sometimes actually come down to who is available and willing to put in the time. Also, since much of the offstage work is done by those involved in the production, offstage skills are likely to be a factor in casting decisions.

It’s an unfortunate fact that community theater groups tend to be notoriously cliquish. Many are run by groups of cronies who take turns starring in and/or directing show after show after show. Once a group like this becomes entrenched, it can be nearly impossible for outsiders to get roles. So outsiders stop trying.

I’ve seen community groups that cast essentially the same people in every show, sometimes out of necessity but often just because that’s what they do. It’s common practice for directors to cast spouses and friends and family, regardless of the availability of more talented actors.

Sometimes casting decisions come down to expediency. I’ve known groups to cast spouses in leads simply because they knew it would be a way to guarantee both would be at all rehearsals. I knew one group that always cast the same non-singer in a small role in every production … because the guy had his own tools and was willing to construct sets. I once saw a director decide between two equally matched players because one of them had a pickup truck for hauling stuff.

Participation Points

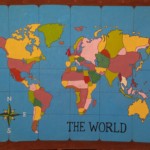

With both community theater and school productions, finding people who are willing to do additional work is crucial. I can’t think of a single production I’ve been involved in that hasn’t involved extra volunteer work. In Seussical, I helped construct some large set pieces. For Shrek, The Musical, I painted the “Freak Flag.” For The King and I, I painted the two schoolroom maps, fabricated an easel to hold them, built Simon Legree’s sword and also built a last-minute sailing ship. When members of my family are in productions, we always try to pitch in with costumes and props and other “side jobs.”

In our recent experience with Aladdin Jr., in which all three of my kids had lead parts, I designed the set, designed and built the “royal box,” and fabricated props (including swords and foam-rubber bread loaves). On top of that, I produced the program (a 20-hour job) and built and sculpted the “Cave of Wonders” set piece (an 18-hour job). I also did specialty makeup for dress rehearsals and all performances.

I have helped with every single school production that any of my kids have ever been in. Should offstage participation have an impact on a director’s decision about who to pick for a particular role? I think the answer should probably be: sometimes.

Casting Consequences

A while ago, I auditioned for a community theater show. After callbacks, I discovered that—for only the second time in my musical theater career—I had been offered a non-singing role. (The first time was with the same group … a trend I would prefer not to continue.) After I turned down the role, the assistant director said, “We’d still really like you to help with the sets.”

Um, no.

If I’m involved in a show with a community theater group, I’m happy to contribute wherever and whenever I can. But I don’t do musical theater to take non-singing roles. This particular show was chock full of great parts for “grownup male” singers. If you want me involved, make sure I’m involved. But don’t give the leads and even the secondary characters to all your friends and family members and then expect me to put in hours on your set.

More Consequences

Not too long ago, two of our children were being considered for major roles in a school musical. Since I’d pitched in on previous shows, the director asked me to take charge of a major scene-shop project—one that would require almost 100 hours to do right. The callback list suggested that both of my teens were being considered for major roles. When the cast list came out, however, it turned out that my boys were passed over in favor of actors who (in my opinion) were just plain wrong for those parts.

Both of my kids were assigned to ensemble roles—in spite of the fact that they had voices (and other talents) better suited for roles that were given to other actors. With just one exception, the director had miscast every main lead in the show. Think Russell Crowe … as Annie. Predictably, she ended up having to cut whole musical numbers because of mismatches with the performers’ vocal ranges. And yet I was apparently still expected to dedicate my nights and weekends for the next three months to a show that can only turn out to be another round of audience abuse.

Um, no.

What Are the Consequences?

A helpful hint to both school and community theater groups: when you make casting decisions, you’re determining how successful (or unsuccessful) your production will be. If you cast your friends or favorites over more talented actors, you’d better be certain that they have the mojo to carry the show. If you award parts based on who needs the part—regardless of who is the best possible choice—you shouldn’t be surprised when others lose faith in the productions you put on the stage.

Also, unless you have an unlimited budget as well as an unlimited supply of skillful volunteers, it’s probably best if you make sure that the people you cast are willing and able to put in the work so that all the critical pieces of the production fall in place in time for opening night.

And above all, please don’t abuse your audiences by casting leads who can’t sing, or can’t sing the parts you’ve given them. That’s a perfect way to ensure that fewer and fewer people buy tickets the next time around.